Insert Headline

Insert text here.

Insert Headline

Insert text here.

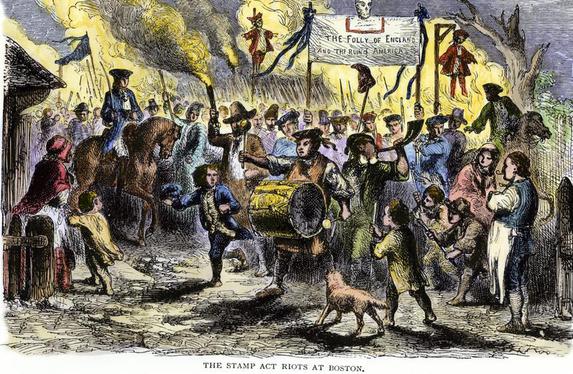

The Stamp Act Riots, Part One

by David J Samuels | September 12 , 2025

I’ve been in the tourism business in Boston since 1999. The story of riots and mob actions in Boston during the Imperial Crisis (1760 to 1775) and before (including the annual Pope’s Day celebration) always interested me and amused me and I shared those stories with our audiences with that in mind. They made for entertaining stories. However, over the years, my perspective on these stories has changed as I view them in the light of the present situation in the US and around the world.

Split into two posts, one for each of the two riots, you will find the story of the Stamp Act Riots of 1765 as best I can tell it. I encourage you to both enjoy the story and see if there are any parallels you can draw between these events and our current times. After all, it is the job of the historical interpreter to make the past relatable to the audiences of today.

And don’t forget to join us on a Tour of the Freedom Trail on your next visit to Boston! We hope to see you soon!

David J Samuels

Founder & Managing Partner

The Histrionic Academy, LLC

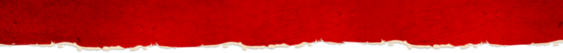

The Stamp Act Riots came out of a protest by American Colonists in Boston, Massachusetts, against a law known as the “Stamp Act” which required all paper goods be “Stamped” and that this stamp be paid for. It was part of an effort by the British government to raise funds to replenish their accounts after several costly wars fought in the American colonies, the last one known as the French & Indian War.

Unfortunately for the British Government, they proposed this tax during an economic downturn in Boston. The end of military operations in Northeastern America in 1760 had caused many to lose a significant portion of their income. This was due to the loss of lucrative military contracts for the “Better Sort”. For the “Lesser Sort”, this loss translated into a loss of jobs.

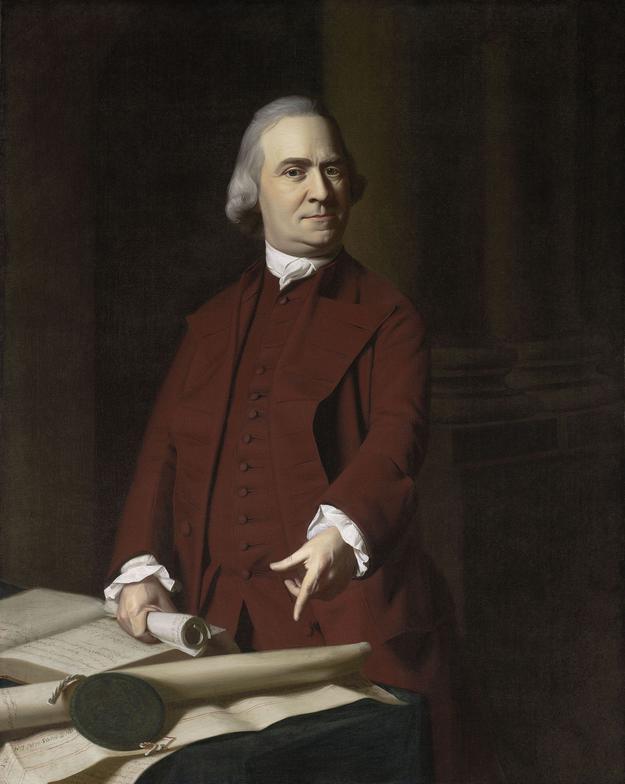

In August of 1765, a protest was organized. While Samuel Adams and his allies may (or may not) have had the best of intentions for a peaceful protest, things got out of hand and led to two incidents of intense politically motivated mob violence roughly two weeks apart.

Background

The Stamp Act Riots Part One: August 14th & 15th, 1765

Sensing worse to come, Sheriff Greenleaf convinced Andrew Oliver and his wife and children to leave their house. No sooner had they fled when the mob arrived. The now officially riotous mob beheaded Oliver’s effigy, built a bonfire from scraps of items they’d taken from his office, and burned the effigy. They broke into his stables and dragged his chaise out to the bonfire with the intention of burning that, too. Some of the men convinced the others that would be going too far, so instead the rioters burned one of the doors of the chaise and some of its cushions.

Rioters smashed the expensive glass windows of the house, tore down the garden fence, destroyed fruit trees, and tore down a gazebo.

Main Sources

By 5am on Wednesday morning, 14 August 1765, a tree designated the “Liberty Tree” was already decorated for the day’s protest and a crowd was starting to gather.

From one branch hung a boot with the figure of a devil in it. This was to represent Lord Bute, who many in the colonies believed had the ear of King George III and was using that access to urge the young king to mistreat the colonies. In the devil figure’s hand was a copy of the Stamp Act.

8/15/1765

Whig (Patriot) leaders feared both making a martyr out of Andrew Oliver and also feared the kind of violent anarchy they’d witnessed. Their next move was more reasoned and controlled. On Thursday, August 15th, they condemned the violence of the previous day, but also repeated their call for Andrew Oliver to resign. At first, he refused and told them he resented their lack of support while the mob had been attacking his home.

By 9pm Thursday evening, a crowd of men and women were gathered outside of Oliver’s house once more. They were chanting about “Liberty and Property”. Oliver sent out a note, one he later said he promised to delay taking office as Stamp Tax Master until he could communicate with the government in London about the public outcry over the Stamp Act. The mob somehow decided that he promised to send his resignation to London on the next ship. Mission accomplished, they moved on to the house of Lieutenant Governor and Chief Justice Thomas Hutchinson. When they arrived, they began to beat on his door and demand that he come out and swear that he had opposed the Stamp Act. Hutchinson stubbornly refused to be intimidated and waited for the destruction to begin. But before it could start, one of his neighbors shouted to the mob that they’d seen him fleeing in his carriage. This seemed to take the wind from the mob’s sails and they dispersed. But the mob was not finished with Thomas Hutchinson.

“What greater joy did New England see,

Than a Stamp Man hanging on a tree”

1. Patriots by AJ Langguth

2. Cradle of Violence by Russell Bourne

3. “Ordinary Americans” on Great Courses

8/14/1765

Under the effigy of Oliver was a sign that said:

“He that takes this down is an enemy to his country”

From another branch hung an effigy of Andrew Oliver, the newly appointed Stamp Tax Master. Ironically, like his brother-in-law, Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson, Andrew Oliver had initially opposed the Stamp Act because he knew it would be extremely unpopular. However, when the Stamp Act was passed, Andrew Oliver used it to his advantage. The Hutchinsons and the Olivers had been active in Massachusetts politics for decades and had learned to use those politics to their advantage. In this case, Andrew Oliver readily accepted the appointment as Stamp Tax Master, knowing it would be a very lucrative position, drawing a significant salary. The colonists did not approve.To his effigy hanging from the Liberty Tree was pinned the following rhyme:

The protest began as a bit of a street performance. Shopkeepers and farmers who brought their goods to market were forced to kneel before the Liberty Tree while the effigy of Andrew Oliver was used as a puppet to stamp their goods.

Thomas Hutchinson, who was not only Lieutenant Governor, but also Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, sent Suffolk County Sheriff Stephen Greenleaf to take down the effigy of Andrew Oliver. Sheriff Greenleaf attempted to do so, but the crowd was too large for Greenleaf and his men to safely carry out Hutchinson’s instructions. Though members of the Governor’s Council attempted to shame Greenleaf into taking on the crowd, he steadfastly refused.

Late in the afternoon, Hutchinson got his wish… sort of. The effigy of his brother-in-law Andrew had been taken down. Unfortunately for both Hutchinson and especially his brother-in-law, the effigy had been nailed to a board and was being carried at the head of a crowd of about forty or fifty sailors, laborers, dock workers, apprentices, servants, and likely at least a few slaves as well. This crowd marched down to the harbor, to a building built there by Oliver (which the people believed he intended to be his Stamp office) and spent half an hour tearing it down.

The mob was discouraged from hunting through the streets of Boston for Andrew Oliver. Instead, the mob, by now inside Oliver’s house, helped themselves to his store of liquor and then destroyed the Oliver family’s expensive looking glass, said to be the largest looking glass in America.

Meanwhile, Governor Francis Bernard ordered that militia drummers were to be sent out to beat an alarm. His orders, however, couldn’t be carried out because the drummers were among the rioters! Instead, Lieutenant Governor and Chief Justice Thomas Hutchinson dragged Sheriff Stephen Greenleaf to the Oliver residence with the intention of ordering the mob to disperse. But when the two arrived at their destination and Hutchinson tried to order the mob to disperse, the crowd started shouting “To your arms, boys!” and began to pelt Hutchinson and Greenleaf with stones, forcing the two men to retreat.

After another hour spent destroying Andrew Oliver’s home, the mob dispersed.